Somewhere in between the classic circuits and iconic formations of the world class bouldering destination of Rocklands, South Africa, lies a hidden realm of dusty caves home to a different kind of climb, for a far different breed of climber. There are no carefully curated trails or straightforward directions on a mainstream climbing specific app to tell you how to get there, rather just some vague Instagram posts from strangers who won’t respond to your DMs, or the occasional GPS coordinates if you get particularly lucky. That is where you find the boulder problems Tom, Pete, Lor, and I travelled halfway around the world for: the ones defined not by the features that are, but by the space where the rock is not. Those are the crack boulders.

It wasn’t just the projects that existed in that nebulous space between, but a theme for the trip as a whole, as it shifted through a spectrum of experiences that can only be described as something in between a kaleidoscope of extremes. It also defined us: four passionate eccentrics devoted to an obscure niche in an already niche sport– so much so that they all somehow made it into functional careers. Who else but us would travel to the diametrically opposite side of the earth to go crack bouldering of all things? and how did such an outrageous trip even come to be?

It began, like so many of my stories do, with a project that refused to let go. Rewind the clock six months and Tom and I were just a few days into our first season ever climbing together, teamed up for another showdown against the notorious desert crack testpiece Stranger than Fiction. After both of our respective climbing partners, Pete and Lor, had sent the previous year, it just made sense that we should climb together. We were something in between strangers and friends, having orbited around the same people and places for years, and yet never actually sharing a rope. Now that we had, it was clearly the beginning of the kind of climbing partnership that would last the tests of distance and time.

As we stood around the kitchen eating our dinner one fateful night, talking about cracks as people like us do, Tom showed me pictures of some lines that had recently caught his eye. He was deep in the backlogs of the Instagram of Ignacio Mulero, a mysterious Spaniard who was on something of a solo mission to develop cutting edge crack boulders in Rocklands, while the rest of the world stuck to their standard crimps and dynos. The photos looked otherworldly, the stuff crackheads like us dream of. What little beta Mulero had publicly shared was enough that Tom was already planning a summer trip with Pete to try some of Mulero’s lines, and further investigate the area’s potential for more.

Take me with you. I immediately thought. I couldn’t think of a trip more worth taking; it checked every box. Travel to a new corner of the globe to do my favorite kind of climbing, but in a style where I still had a lot to learn? Yes please. More than that though, I wanted to climb more with Tom, and if Pete was even half as fun, I wanted to climb with him too.

In the end I managed to score an invite and so there we were: two people who were just getting to know each other and one who I didn’t really know at all, impulsively planning a month-long trip to the other side of the world based off a few Instagram photos that looked pretty cool. It was exactly the kind of reckless leap of faith that would surely be memorable, either because it worked out brilliantly, crashed and burned spectacularly, or perhaps did a little bit of both and ended up as something in between.

We ended our season on Stranger no longer strangers, but as people so connected that even the six month wait until the Rocklands trip was six months too long to wait. I headed south to Mexico for the first half of winter for some limestone sport climbing on what was supposed to be sort of a vacation, but pretty soon the endless rainy days in a not-so-waterproof tent with almost no one else around to distract me got heavy. Why had I left behind my beautiful, vibrant Utah desert to live in this soggy gray cloud? It had had to happen of course, but I still mourned the end of my fall season on Stranger with Tom as if I had forever lost something precious and irreplacable.

Seeking some kind of reprieve from the gloom, I phoned up my good friend Lor who was having a challenging season of their own back in the United States. Stranger had been what had brought me and them together too, when two intense seasons of projecting brought us as close as two friends can get. Since then, it had also been what had kept us apart, as our objectives no longer aligned while I was still so wholeheartedly committed to a cause they had moved on from. Our inability to resync eternally pained us both. We had been trying to get the team back together ever since, but life just always got in the way.

I told them about Rocklands, and to my surprise, they asked if they could join. They didn’t know the Wide Boyz like I did, but had met them out at Stranger: the same place we had all connected. Suddenly, it all felt like fate. Four people so desperate to climb together that they were willing to traverse continents and oceans to give this novel idea a try.

After I left behind the moodiness that was my trip to Guadalcázar, and a whirlwind trip to Egypt shortly after, I dedicated myself to the grind. For two years now I’d been pouring as much of myself as I could into training for Stranger, but thus far it had been a constant tease of two steps forward, one step back. Just as I would start to gain momentum, my chronic elbow cartilage injury would reawaken and I would once more become limited in the volume, intensity, or type of climbing I could do. Something or other was always off-limits, creating ever present barriers to ever make significant progress in my climbing.

I had been to so many false summits with the recovery process, ridden so many waves and fought through so many setbacks that over time I’d stopped even believing there was light at the end of this particular tunnel. I still worked as hard as ever, but in my heart, I expected only more tunnel. I would never be fully healed, thus it would always hold me back. I persevered like there was no tomorrow, but only because there was no acceptable alternative, not because I actually believed in it. Such a mindset was a far cry from the idealistic mantras I used to live and die by, such as this Terrence McKenna quote that once upon a time I’d built my entire ethos around:

“Nature loves courage. You make the commitment and nature will respond to that commitment by removing impossible obstacles. Dream the impossible dream and the world will not grind you under, it will lift you up. This is the trick. This is what all these teachers and philosophers who really counted, who really touched the alchemical gold, this is what they understood. This is the shamanic dance in the waterfall. This is how magic is done. By hurling yourself into the abyss and discovering it’s a feather bed.”

No feather bed caught me–but by spring’s end something had shifted. I was maybe, just maybe, actually getting somewhere. The heavy things I picked up were heavier than they had ever been. I could do harder boulders on the gym boards. I could train more days per week and still climb outside. I took rest days because my whole body needed it, not just because my elbow hurt. This might finally be something other than just more tunnel, but I had been let down too many times before to really believe it. Rocklands would have to be the true test, both that I might not be injured forever, and that I might actually have gotten a bit stronger.

My injury aside, going into the Rocklands trip I already knew I was going to have some other battles to fight within myself too. I’d had a complicated relationship with bouldering in my early twenties, almost burning bridges with friends and entirely burning out myself, so I’d written it off as just too toxic for me. I blamed it for bringing out a version of myself that I never wanted to be again: overly competetive and in it for all the wrong reasons. I spent the next decade subduing those negative parts of myself, and putting in the work to separate my self-worth from my climbing so that I would never again be so focused on an outcome that I became blind to the beauty of the actual experience. I even came back to bouldering with a short season in Bishop in 2023, where my improved perspective allowed me to finally achieve the lifetime goal of climbing V10 that had haunted me all those years ago.

It was the final step in repairing my relationship with bouldering, not because I ticked the box of an arbitrary grade, but because the toxic one in the relationship was never bouldering, it had always been me.

That problematic part of me will probably never truly be gone, but is now more like an intrusive thought, easy to ignore because I know it’s wrong. It’s the devil that sits on my shoulder, whispering treason in my ear–your worth is determined by sends and status, not by your soul. I don’t listen anymore, I know better, but that doesn’t mean the devil isn’t there.

It was going to haunt me in Rocklands. I was going to be trying climbs that were above my skill level in a style I barely knew, with three people who were all much better than me. I went into the trip knowing that I was going to get humbled, and that it would take constant work not to let that devil’s words creep into my psyche. I knew all of this, I knew it. I knew it, and I prepared for it, and yet it still happened almost immediately.

For the first week of the trip, every boulder we went to was the same experience, no matter if it was V6 or V11. Pete would flash it. Tom would get it second try, if not flash it. Lor would either flash it, or do it quickly, and then I would leave empty handed. I was climbing extremely well for myself and by all accounts I should have been proud, yet the intrusive thoughts whispered:

Who are you kidding? You don’t belong here with them. They don’t want to wait for you to keep sieging this thing that they finished hours ago. Everyone is bored. They aren’t having fun because of you. Your climbing doesn’t matter, because it’s not as impressive. You don’t deserve the same amount of support that you are giving. You’re wasting their time, holding them back, getting in the way, clipping their wings…

I still had enough clarity to know it wasn’t true, but the stray negative thought would sometimes still break through my defenses and I struggled to advocate for my own climbing as the group began to be pulled in different directions of who wanted to climb on what.

Thankfully where I was struggling, my companions were always ready to step in and help me get out of my own way. Pete spoke about my climbing plans as if they were facts set in stone, always asking me when I was going to my projects so that everyone else could plan around them, or corralling the group to make sure we had time. Tom was always ready with beta or a pep talk, always attentively spotting me or moving pads the moment I’d left the ground. Lor could read my emotions like a book and was constantly opening the doors to talk through the ways I was struggling right when I needed it. No matter what, someone always had the camera rolling whenever I pulled off the ground, and the right thing to say when I fell off. My friends met me in the space between doubt and belief, and little by little all of those small acts of support and kindness added up. Eventually they were enough of a lifeline that I could pull myself out of the turbulent waters of my own mind.

As I won victories over my demons, my climbing took off in response. After a few consecutive rest days, much needed after nearly digging myself into an irreparable fatigue hole, I finally hit my stride.

First I sent Ace Hotel, a V9 that had utterly shut me down on my first session. A short but powerful roof crack ending in series of kneebar contortions, it had given me trouble at the thin crux where my large hands struggled to hold a marginal paddle hand jam. With a rested body and colder temperatures, this time I sent it as a warm up. I had switched how I was holding a few of the jams– a subtle change from thumbs-up to a more counter intuitive thumbs-down position that suddenly made a previously effortful few moves feel like rests.

More and more small things like those adjustments clicked into place, as the gaps in my limited knowledge of roof crack climbing filled in, fast tracked by their necessity on such difficult problems. Before this trip I’d only had a handful of days on crack trainers and roof boulders here and there, and thus confusion had always marked my experience. Thumbs up or down? Scrunched up or stretched out? Move in a hand foot hand foot, or a hand hand foot foot sequence? It was like trying to understand a foreign dialect of a language I already spoke, something in between the familiar and the unknown. I knew the words, but just needed more exposure to fully understand how to pronounce them right.

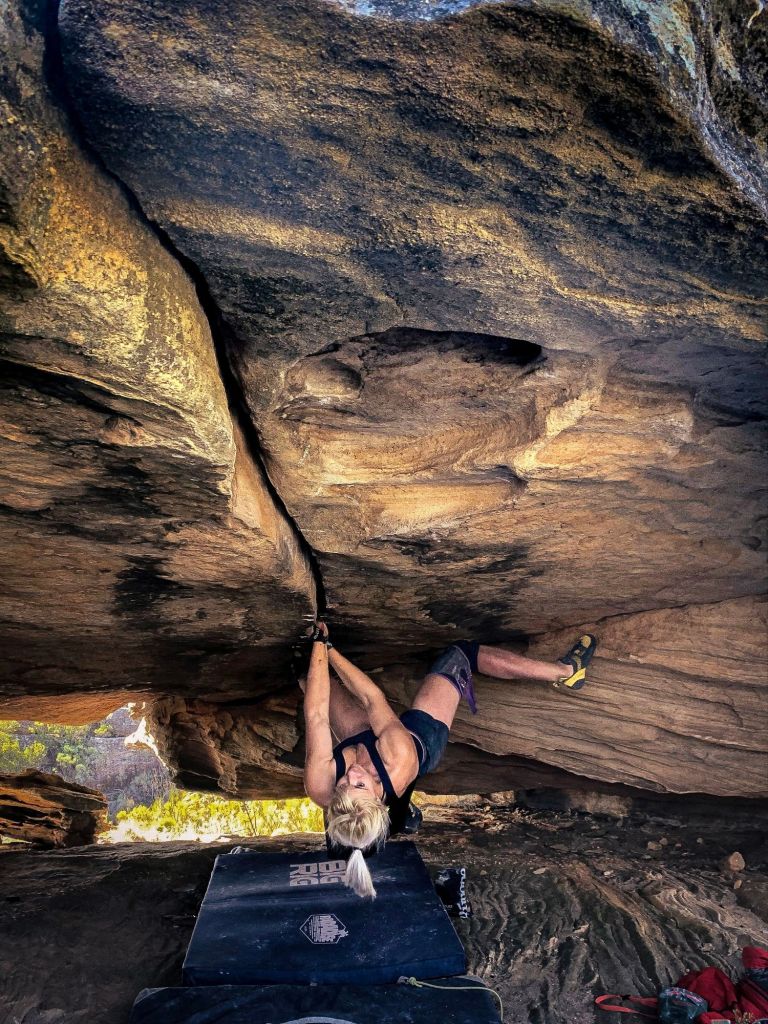

The next day I did the Gecko House, a V8 offwidth roof that required a sustained shuffling of the wide pony technique (where your hands are stacked on top of each other with one foot on either side as you shuffle sideways one limb at a time, constantly holding a strenuous sit up with your core). I’d done maybe two or three consecutive moves like it before, but never anything sustained. Disbelief of my own performance gripped me as I screamed my way around the final fist jams to top it out.

V8 is a hard grade for me, and I just did one in a completely new style? I was barely a 5.11+ offwidth climber on a good day, so where had this come from? I was looking at myself in a mirror, but not quite recognizing my own reflection. It was the first indicator of a subtle paradigm shift in my perception of my climbing ability that was happening, but just like believing in more tunnel at the end of the tunnel with my injury and getting stronger, I wasn’t quite ready to see it yet.

The next day I sent X, a V11, in a single session. It suited my style well (mostly finger locks), and it was sloppy because I dabbed, and it was probably soft… but the paradigm shifted a little more.

Could it be? Could it actually be that maybe, just maybe I had written myself off too soon?

To be clear, I had never given up. I was never about to stop trying to get better, stronger, more skilled. I just thought I was fighting for maybe a 0.01% improvement; that if I could just scrap together that much more, I could do Stranger and that would be enough. “Dream the impossible dream,” hadn’t felt honest in quite some time. I still believed it for everyone else, but somehow I had become the exception to my own mantras. I had forgotten how to dance the shamanic dance in the waterfall. There was no more alchemical gold for me, just more and more tunnels.

As Lor and I walked away from X, talking about philosophy as people like us do, I voiced my fragile hope: What if there was more than 0.01% left for me to gain? What if there was a lot more? In all my years bouldering, in two and a half decades of climbing, V10 had always been the goal. I’d never even conceived of climbing harder than that. It was too big to even be the dream, and now I had just done it. More pieces of the shift fit together: changes that had happened so slowly over such a long period of time that I had been too zoomed in to ever see the forest for the trees. Things like how V9 used to be my absolute limit, a grade I could only do in exactly my style on my very best days, and now it was the grade of something I’d try and do in a session in any style. How I’d never have tried a V11 before, because I just assumed it was too hard, and yet I had started my day with at least some degree of confidence in my ability to do X before having ever even pulled on. What was that? Where had that come from?

As we strolled along the well-worn path back from the Sassies, a rare break from our usual bushwhacking approaches, I was walking on air. It wasn’t because of the achievement, but from the glimpse at a vision for the future where I remembered how to believe.

“Dream the impossible dream,” eh? I’d wanted to believe in it so badly, for so long, as I’d stumbled my way through the tunnel year after year. It turns out belief is a lot easier on bright days and in fair weather, but when you are lost in the dark and you need it the most… I don’t think I was quite strong enough to hold onto it then, but neither was I so weak as to fully release it. Those years in the tunnel my belief in myself and my dreams was something in between holding on and letting go. I could keep forging ahead in a detached sort of way, but I always knew a crucial piece was missing.

So there I was, as far from home as a girl can get, and yet I had finally found a long-lost piece of myself that felt more like my home than crossing any border or flying any national flag.

Scattered days of rain and rest were to follow. The list of cracks we had to do was never a particularly long one, thrown together as it was by random Instagram photos and word of mouth through Mulero and his friends. Some well-seasoned Rocklands climbers insisted that every crack boulder had already been found, that the rock just doesn’t naturally split that way. He claimed that the ones already done were anomalies rather than the norm. We suspected they just might not be looking in the right places.

During the first half of the trip, when we were still tracking down all our projects, a large portion of our days was often spent just locating the boulders—bushwhacking in circles for hours, only to eventually find what we were looking for in an unassuming cave right off a major trail, hidden in plain sight. We never saw another soul aside from the enigmatic Mulero, who would appear seemingly at random from time to time, always eager to watch us climb on his routes. We were certainly the first repeats some of his harder boulders had seen, and I can only imagine how exciting it must have been to have four more sets of hands pick up a torch he had carried by himself for so long.

Despite what others had said about the area being tapped out, Mulero was always out searching for new cracks, and we knew he had many secret projects yet to be finished. We started looking around for new lines ourselves, now that we had begun to understand the kinds of formations to look for. Sure enough, unclimbed cracks were everywhere, if you just had the right set of eyes.

We were far more focused on cleaning up each of our individual projects than new routing though, so we arranged our climbing schedule to stagger our climbing times and days so as to share the pads and shade appropriately. It was the only real system available but it meant that we never actually took any days off. Out of the 29 days that we were in Rocklands, I went to the crag on 28 of them, missing just one for some sight-seeing in Cape Town. That meant that even on my rest days I was still usually hiking several miles, always spotting or moving around crash pads, and generally hanging out in the cold; aka not truly resting. That all gas, no brakes frantic tempo packed a lot into just a few short weeks, for not a day was thrown away; no moment wasted or without value. Life was really being lived to the fullest out there, but that kind of pace can only exist within the bubble of a trip, and even then, is unsustainable after a time.

Since the day I arrived, I had been giving everything I had to this trip. Trying problems always at my limit had me on the edge of physical exhaustion, and checking my ego as I fought my old demons took a constant effort, even when I was winning the battle. I couldn’t imagine three people I’d rather have been with, but travelling as a team so closely bonded had its costs too. It’s easier for a trip to be all vacation smiles and sunshine when you don’t know your companions very well, because real life gets compartmentalized away to just focus on the climbing. It may be fun, but to some extent it’s also fake.

When you’re out there with people you really care about however, trapped with one car, in one small cabin together, you’re there for the real stuff. You don’t get to just go to the crag and pretend there’s nothing more important about your day than rock climbing, because people who genuinely care can see right through that mask. Come hell or high water, we were all on this journey together, and we all had our own demons to face at one point or another.

If I were given a choice between a fairytale trip and a gritty honest one, filled with all the highs and lows of real life, I’d choose the latter every time. There’s so much more to be said for growth over glory. A good adventure should be something in between the struggles and the success, the darkness and light.

In the end though we are all only human, and by the last week of the trip we were all running on fumes from how much life had been packed into such a short time. We still hungered for our projects of course, and showed up to make the most of the borrowed time we had left with one another, but we were all feeling a bit beat down.

While we had already had a wildly successful trip across the board, there remained just a bit of unfinished business for each of us to truly make our crack tour feel complete. I had put several days into a very long V11 roof crack called Mkhulu and was falling at the very end, and was torn between trying to finish it off, or going after another V11 called King Kraken that was much more my style. On the one hand Mkhulu was perhaps the crown jewel of the trip in terms of highest quality climbing, and would have been the most meaningful thing I could have sent because it so closely resembled some of the hardest climbing on Stranger. On the other hand, because it targeted some of my weaknesses, I could easily throw away the rest of my trip just to fall off the same last move eight more times.

King Kraken however, offered a different temptation. I knew from the get go that I had a good shot at the diabolical finger crack because it suited my strengths just fine and I had quite easily already done its V9 stand start, Awaken the Kraken. While still endurance-y and with a healthy dose of paddle hands, its crux was pure bouldering and the finger locks were too perfect to pass up. The Kraken called to me with the siren song of the sea, promising the perfect challenge to try and put together with the two days I had left. If I climbed at my very best, I knew I could do it. If I showed up with anything less, I would walk away with nothing but a few new gobis and a whole lot of what ifs.

In the end King Kraken called louder, if for no better reason than that it was just a bit more fun. Still slightly dragging from an adventurous weekend in Cape Town, I started one of my last sessions barely able to do the easiest part of the climb. The world was a little fuzzy around the edges and none of my rock-solid beta from the previous session was working anymore. I had spent hours unlocking a proven sequence with Lor, good enough for them to have already sent, and yet now I couldn’t repeat it.

Pete, who hadn’t been with us before, crawled into the cave with me to try and diagnose the problem, having climbed the crux sequence with completely different beta when he flashed the boulder. Crack master that he is, he quickly identified why I was struggling with the crucial foot jam, even going so far as to put his shoes on and climb through the sequence so I could watch his exact beta. Subtle differences emerged– he pointed his toe here, and dropped his heel there. I studied all the nuances of his movements like I was about to be tested on them, because in a sense I was.

I pulled into the strenuous position that had spat me out so many times before, and the crux jam went from desperately insecure to something I would never fall out of. At this point I played a delicate game however, deciding how much to try now versus preventing myself from getting too fatigued to have another shot on the last day. I was pretty tired already. Maybe just once more.

My mind went back to a statement from a street performer in Cape Town the previous day: “Check this out, I’m about to be amazing!” At the time I had joked about using his catch phrase for my climbing, but I hadn’t really meant it because this whole time I’d been so focused on the opposite: staying humble, no egos allowed.

What if that was the kind of energy I needed right now though? What if there was something in between my meek humility on this trip and the toxic rage from my youth? The paradigm shifted a little more. Why not try a little reckless egotism? It’s just a form of belief, after all, and didn’t that stranger’s bravado mirror the exact kind of belief I’d once wielded like a weapon? Maybe he had stumbled across the alchemical gold without even realizing it.

“I’m about to be amazing,” a shy voice whispered in my head as I pulled off the ground and the world around me faded away, leaving just the void of a perfect crack stretching out before me into the abyss. Maybe there really was a feather bed out there; maybe nature really does love courage. I made the commitment: every last drop of energy and belief that I had in me. Every jam from that first finger lock to the last perfect hand demanded a fight, but when it really mattered here at the final hour, I made no mistakes. I dared to believe in the dream, and in myself, and a few minutes later I stood on top of the hardest boulder I’d ever done.

I could deny the paradigm shift no longer: somewhere along the way on this trip I had become a better climber. Not only that, but now I didn’t just believe I could still become an even better one, I knew it.

On X it hadn’t been about the grade, but now on the Kraken combined with everything else I had done on this trip, the grade did matter. At the end of our fall season on Stranger, Tom had been convinced that I just needed to boulder one grade harder to be able do the route. On paper it seemed realistic, a year of dedicated training for just one grade? Why not. I wasn’t trying to jump from V10 to V11 outdoors, or to send a certain benchmark on the Kilter Board, but that idea of ‘one grade harder to do Stranger,’ was always on my mind. It was the secret goal, even when I still believed I was just fighting for that 0.01%. I never really knew if I could boulder one grade harder, except… now I had done exactly that.

If I said the trip started out feeling like fate, well… maybe this time we’ll call it full circle instead. While Stranger may have brought us together and inspired my direction, Rocklands had bonded us for good and gave me the compass to get there.

.

By the end of our trip, the cracks we could do were all done, and the ones we couldn’t were left for another time. Mkhulu alone was worth coming back for, and no doubt Mulero was out there somewhere digging out a new cave where he had just found the next great line. For now though, we decided to spend our final day in a popular area climbing regular boulders, just to see what all the fuss was about.

The sheer volume of other climbers milling about was a shock to the system, their loud cries of Allez! Gamba! And Venga! a cacophony of overstimulation for a tired quartet that had just spent the last few weeks squirreled away in their own isolated little bubble.

As I laid on the pads underneath a warm up boulder, I couldn’t imagine actually putting on my shoes. After the Kraken I had fallen ill, the last of what I had left to give, finally gone. I had no more skin on my fingers, strength in my muscles, nor spring in my step. I’ve just got nothing left, I thought to myself. This was it. I had reached the end.

What if I did it though, what if I put my shoes on? I thought almost as a joke, for how unreasonable it seemed. I’ve got nothing left, but what if I still put my shoes on and climbed one more boulder? Everything thus far on the trip had taken me to this moment on the edge of what I was, but if I could take one more step, climb just one more problem, it meant going beyond that end and forging myself into something more. Evolving. Going to that place where the real magic in climbing truly lies, and I had a chance now to taste it.

Knees weak, arms shaking, one approach shoe and then the other was slowly replaced with Katanas. Just try and do one more boulder. I climbed up the warmup, and although my blood was molasses, by the time I scrambled back down I felt just a little bit less tired than before. Maybe one more boulder.

One turned into another, and another, and I made it through the entire day until the sun hung low in the sky and my skin was so thin no amount of chalk could keep it dry. Now this, this was truly the end: not an end like a wall, where you are stopped because you failed, but an end like a summit, where you stop because you succeeded.

.

So how was Rocklands, you ask? That’s not a simple question to answer. Rocklands was something in between pain and joy; struggle and victory; darkness and light. It was something in between the flawless performance trip you would expect from a bunch of professional athletes, and the complicated life trip you would expect from a bunch of regular human beings. It fully broke me down and built me back up into something greater than I was before, but at the cost of everything that I had to give. It changed my perception of who I am and what I am capable of… or perhaps it just reminded me of what I’d known all along but had forgotten. It tested and then deepened my relationships with people I would gladly travel to the other side of the world for over and over again. Rocklands was messy, because real life is messy—it was a place where the cracks weren’t just in the boulders, but in navigating the simple acts of being human. Honestly, I think that’s kind of the sweet spot—far better than tunnels, and closer to gold.

.

The inspiration for the theme for this post, “Something In Between,” is a song I love by the artist Myle that can be heard here:

Finally, for any fellow crackheads who are interested in any of the problems we climbed on our trip, I have created a map with some brief descriptions of all the known crack boulders in Rocklands at the time of our trip that can be found here: https://earth.google.com/earth/d/1aXTp7d-2mXO5XIkQRWHx6eqNNYOOsWVJ?usp=sharing